I recently wrote an extended essay about the political history of quilting and how the feminist movement used quilting specifically and textile techniques generally to change the opportunity and status for women artists within the patriarchal art world. I really enjoyed researching and writing it, and it made me realise that using skills seen as domestic craft work in the context of art to make a feminist political statement has been going on for centuries.

During the 17 and 18th centuries women used quilting and embroidery as a practical necessity, but some used it to convey messages about morality and daily life. Ann Wests’ coverlet c 1820 is a good example of this with its moralistic and religious central panel and small town scenes surrounding it. Womens’ lack of status within society restricted us and our work was seen to be of little aesthetic significance, however Ann West has made herself heard through her textile skills. The Coverlet can be seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

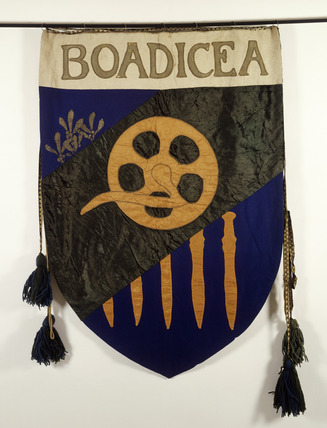

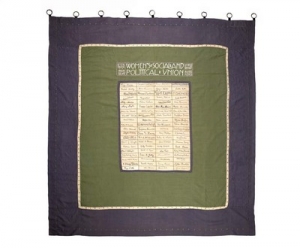

The first suffrage society was formed in 1866 and by 1896 the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society’s (NUWSS) was formed. By 1907 it strengthened its organisational structure and organised a series of marches. Mary Lowndes, a designer, stained glass artist, painter and founding member of The Artists’ Suffrage League and the Women’s Guild of Arts, noted the advantages of women using “dignified womanly skills while making unwomanly demands” in the making of banners for these processions. (Lowndes 1909). Lowndes, amongst other artists including May Morris and Ann Macbeth clearly show how the British Women’s’ Suffrage Movement sought to change patriarchal notions both within the art world and in wider society by using textile processes.

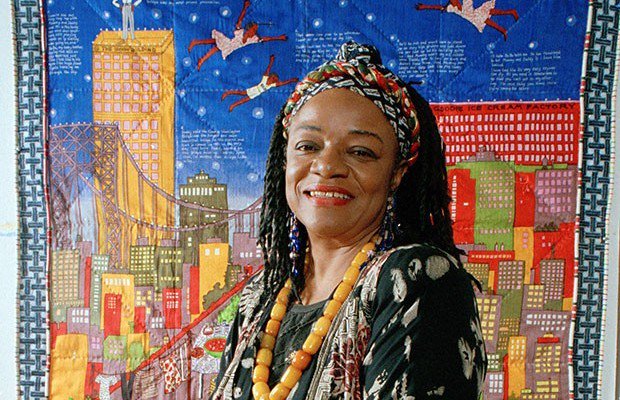

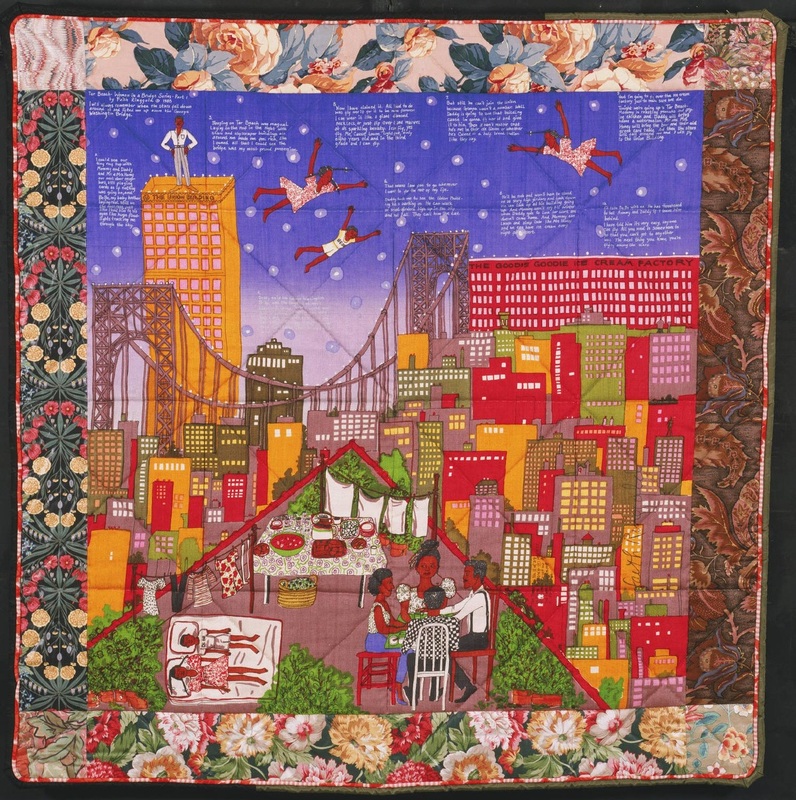

It was in the 1970’s that women once again were seen to be using stitch and textile processes in an organised manner to confront the patriarchal art world. Borzello notes that women’s “resentment” over their role in the art world in the 1960’s culminated in the new wave of feminism. (Borzello, 2000 p. 198). The movement was supported by feminist art theory which had two key themes, firstly patriarchy – the fact that power is in the hands of men, and secondly sexism, discrimination against women. (Hatt and Klonk 2006 p 146). It is with this feminist ideology behind her that Faith Ringgold began to work with textile processes because it allowed her to be free from the mainstream. She wrote

“I was trying to find out : What is women’s art? What would you do as a woman in your art, if you could do anything you wanted to do, and you weren’t looking at the male, white mainstream. You were looking within yourself.” (Ringgold, 1989 in Auther p. 100) .

In the early 70’s, therefore, she along with other feminist artists and supported by feminist theory, began to use textile processes including quilting that were culturally appropriate to her heritage. (Munro 1977 p. 364). In so doing she could articulate her life as a African American woman. (Auther (2010) p 105) Ringgold took this a step further by using the textile processes she learnt from her mother and used by her slave ancestors. The portability of her work became significant to her aim of socially relevant art when she was asked by prominent black intellectuals and activists to market her work directly to college campus galleries. She said

“Feminist art is soft art, lightweight art. This is the contribution women have made that is uniquely theirs.” (Ringgold, 1975) in Auther, p 105)

My essay went on to look at two contemporary textile artists who use quilting – Dorothy Caldwell and Pauline Burbidge, both of whom have influenced my practice.

Burbidge notes that Dorothy Caldwell has ‘developed world-wide textile knowledge and understanding, and [has influenced] her love of mark-making and stitch’. (Burbidge in Pitcher, 2016). Caldwell like Burbidge started her career as an artist in the early 70’s. She was inspired by the surface treatment and staining in Mark Rothko’s painting and influenced by the 1971 Abstract Design in American Quilts exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York. (Lewis, 2014). She was therefore like Burbidge part of the quilt revival movement. Unlike Burbidge though, she is a American born Canadian Artist with involvement in creating alternative art spaces in the early 70’s (Trout in Plaid 2013). She has spent the last 40 years “building a career on staining and stitching cloth”, and transcends, Lewis patriarchally suggests, the “limited boundaries of the medium of textiles”. (Lewis J. 2014). She is, therefore, rooted in 2nd wave feminism and has been a pioneer for many of the contemporary textile processes that we see used by textile artists practicing today such as Alice Fox who cites Caldwell as being influential in her use of earth pigments to dye cloth as well as collecting found objects whilst on location. (Fox, 2015 p.55)

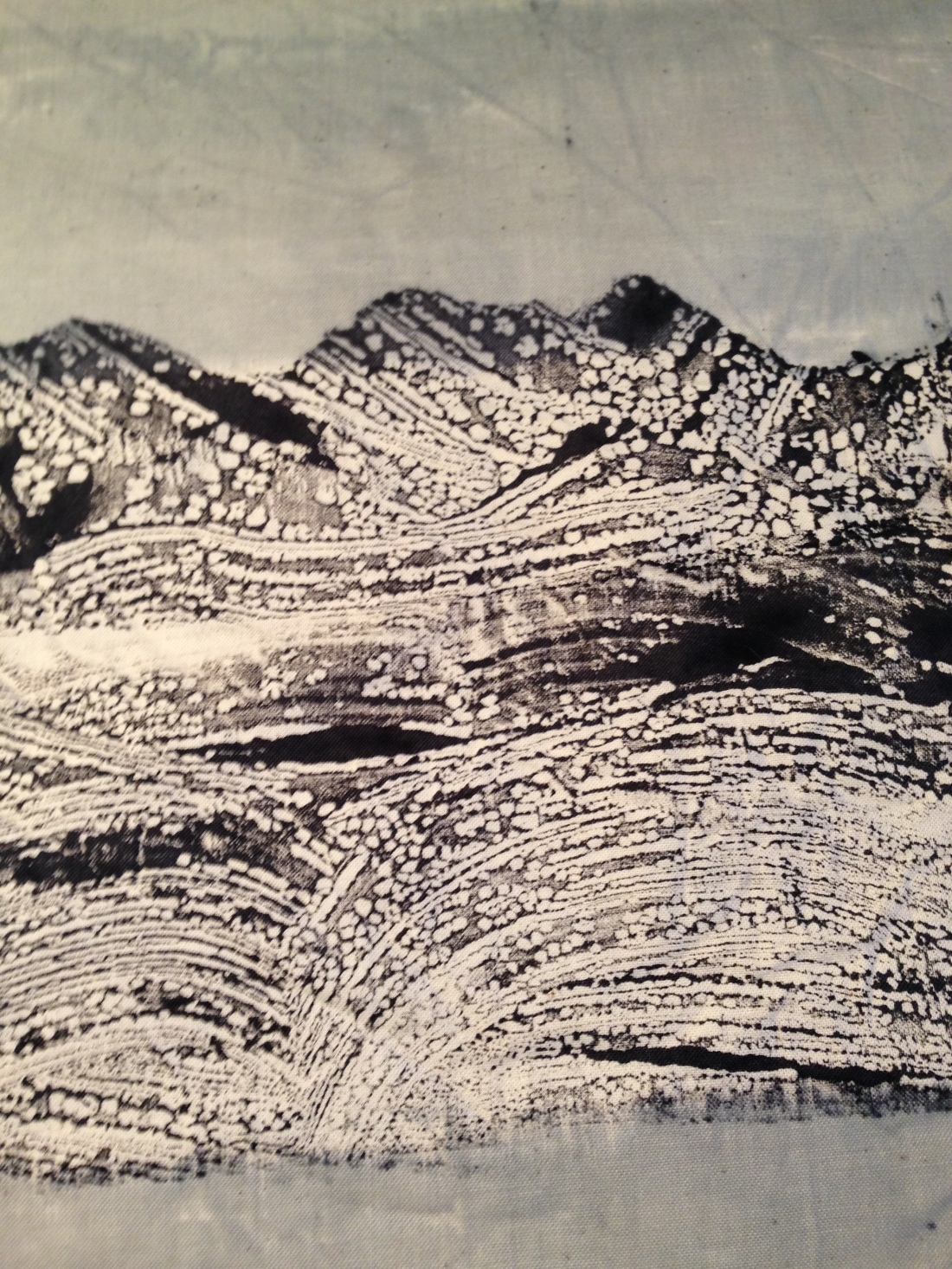

Caldwell says that her work is informed by textile traditions and “ordinary stitching practices such as darning, mending and patching”. (Caldwell, 2018). Her culturally and environmentally focused quilt panels are made in response to places. Her practice is to spend time in a place before she starts to respond to it. She collects found objects during this time as well as developing sketchbooks by staining the pages with soil, dust, leaves etc. She only then starts to work with cloth. Lewis notes that in this way “the landscape is not captured; it is experienced”. (Lewis , 2014 p8).

In my conclusion I noted that Ringgold and other 2nd wave feminist artists made a strategic choice to side step traditional exhibiting spaces the result being that contemporary textile artists have a large choice of exhibiting venues as Caldwell’s and Burbidge’s exhibition lists suggest. Contemporary artists choose between festivals, textile specific shows, galleries and open studios meaning it is no longer a priority to seek to change the patriarchal art world to get their work seen. Women have opened their own doors. This development of alternative exhibiting venues where the patriarchal art world can view this work but not control it may be one of the most influential elements of the Suffragette and 2nd wave feminist legacies to contemporary practitioners. Linda Nochlin asked “Why have there been no great women artists”, and went on to suggest that it was the nature of our patriarchal institutions and “the view of reality which they impose on the human beings that are part of them” that is one of the problems. (Nochlin 1971 in Reilly (ed) p 47). So by bye-passing these art institutions women have created a more equal playing field and womens ingenuity can be seen to prevail.

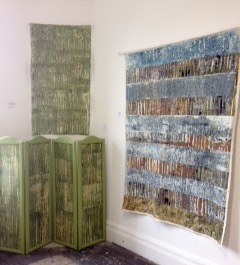

This summer I went up to Steadings Mill where Pauline Burbidge has her annual open studio event with her partner Charlie Poulson. This year they had Dorothy Caldwell as their guest exhibitor. It was a wonderful show and a great example of the above.

Thanks for reading this blog!